The interview was conducted by undergraduate research assistant Fyza Azam.

Fyza Azam: Could you tell me about a course you teach that addresses racialized ecologies?

Anita Girvan: Sure, basically all my courses do, but I’m going to stick to “Environmental Justice and Gender.” It addresses racialized ecologies in terms of who bears the brunt of environmental harms, like environmental racism, and how siting pollutants close to racialized or Indigenous communities tends to be normalized. But it’s also thinking about epistemology or knowledge justice. We’re thinking about how racialized knowledges have been diminished because they have often not entered the academy. Or how solutions to climate change tends to be through white male scientists, or those kinds of derivative knowledges that are shaped by colonial norms of power. I start by grounding in Indigenous places and communities and then looking at mostly women of colour and queer people who are knowledge-holders about environments, and who are also marginalized in those environments.

Fyza Azam: What do you most hope students will get from the course?

Anita Girvan: Drawing on my course syllabus, these are the learning outcomes.

By the end of this course, students will be able to draw upon feminist and gender theories and practices to:

- relate histories of land, legacies of colonization, and gender and race in the making of justice or injustice in these territories. The nations of Lək̓ʷəŋən and W̱SÁNEĆ, which is where I live in so-called Victoria, and then also in other regions of the world.

- demonstrate the role of critical and creative approaches to environmental justice and epistemic, or knowledge justice.

- analyze the role of knowledge systems in relation to and in working with ecologies and fair access to life and livelihoods.

- creatively engage course materials and learning in original ways, as creators of transformation. I would like students to think of themselves as creators, not just sort of talking heads.

- work cooperatively to promote environmental and epistemic justice as a transformative, collective approach to pressing issues. Rather than focusing on individual acts like personal recycling in response to capitalism, we emphasize collective action.

- the last important one is to centre the role of hope as action in combating apathy, anxiety, and “doomism.” When dealing with environmental issues, it tends to get a little doomy-gloomy, so I start off with hope, understandings of hope—as a kind of practice, not as a feeling.

Those are the formal six things but, essentially, I want people to come away thinking of themselves as agents in larger systems: in systems that they might not have signed up for and don’t agree to, but feel themselves as having some role to transform, collectively with others, in positive ways.

Fyza Azam: How have you organized the course? Is there a rhythm or a narrative that shapes it?

Anita Girvan: I think so! All my courses start by grounding wherever we are in Indigenous lands. This course, like others, starts with a grounding in local relations and then expands to transnational contexts and connections.

First, we think with Lək̓ʷəŋən food systems and W̱SÁNEĆ Governance Stories. I share the website with the W̱SÁNEĆ governance stories, and a video of Cheryl Bryce (Songhees) doing land reclamation through plant restoration. That is the first opening salvo of all my courses.

Next, the course centres complexity and complicity, asking how we are complicit in these systems and how we might still practice hope. Before we get into any case studies of environmental justice, we think with some concepts and practices. Sheila Watt-Cloutier, an Inuit activist-scholar, has a podcast called Radical Act of Hope, and Mariame Kaba, a Black feminist abolitionist, has a podcast in which she talks about Hope is a Discipline. People get anxious all the time, and thinking about environmental issues can make you more anxious. To start, we ground ourselves in place and in hope. From this grounding, we consider how we are all in these systems, complicit with them, that we have not voted for them, and yet there are ways of practicing out of them collectively, and with hope as a kind of action.

The next theme is intersectional understandings of queer and trans ecologies and disabled futurities, and thinking across intersections to get into case studies, because the students are asked to think specifically with case studies for their final projects. I present a few case studies from the Democratic Republic of Congo, Palestine, and local cases of Wet’suwet’en resistance here in British Columbia.

The goal is to start here, ground it here, think with concepts of complicity and hope. Go through intersectional understandings, then case studies, and then it’s their turn to do the sort of synthesis around the case studies they’ve chosen.

Fyza Azam: Could you tell me about some of the readings or other texts you assign? How have students responded to them?

Anita Girvan: I always try to find whatever materials there are online for the students to see how to begin to ground themselves in the First Nations lands that we’re in without burdening local nations with educating settlers.

Cheryl Bryce, from the Songhees Nation of Lək̓ʷəŋən peoples, has an on-line video in which she walks and talks about going through the land and preparing these camas bulbs (kwetlal) that she’s done over time immemorial with her family. Some students know about this, and some students have no idea. So that’s sort of interesting to me to see that even the same cohort of students has very different experiences with some Indigenous knowledges of these lands.

Then we read the “four stories of how things came to be,” another set of governance stories in what’s called the Saanich Peninsula, or W̱SÁNEĆ. Those are interesting in how to ground in cedar trees, arbutus, salmon, and all the kinds of larger-than-human relations that are here. The students are very eager to learn about those things. I guess fewer than a quarter have looked at those stories before, and we’re coming into a shared vocabulary and ethics for thinking with them.

The next work we discuss is Alexis Shotwell’s “Complexity and Complicity.” It is a chapter in Against Purity, Living Ethically in Compromised Times. Shotwell talks about how we’re complicit in systems we haven’t signed up for, we’re just born into them, and so we’re sort of predisposed toward feeling guilt. But guilt is not a generative feeling. At the same time, Shotwell insists we shouldn’t attempt to feel ourselves “pure,” or not complicit, because that also doesn’t help us navigate the ethical challenges of being responsible and accountable within these unjust systems. That part is important because sometimes you have people who have this self-righteousness, thinking they have the proper identity or that they know the proper critique.

But if we start thinking with complicity that nobody is purely outside of the systems that are creating degradation to humans and more-than-humans, then it gives us all permission to not be policing each other and calling people out. I find that helps to set the tone for the class, insisting that there are some people who are affected more by power systems because of race and colonization and everything, but that we can also come together and think of ways that we may all be complicit to some degree in some harmful systems. Then again, that complicity doesn’t just stay inside your body, but it goes towards this hope, transformation.

A book I use throughout is All We Can Save: Truth, Courage, and Solutions to Climate Crisis, which two women scientists have edited. It’s mostly works by Indigenous, Black, and people of colour responding to the issues around and how to think with different solutions. There’s poetry as well as essays, so the students really love it. There’s always a challenge at midterm and beyond, like how to get them still to read. But I would say that, in general, they’re engaging well. We do documentary films, as well as podcasts, poems, and essays.

Fyza Azam: What types of assignments do you have?

Anita Girvan: For the first one, I generally do a discussion post. A discussion forum post where they’re introducing themselves and thinking with the first two weeks of readings. Having them ground themselves in these lands, and thinking about how they come to these lands, without reproducing trauma, if they have traumatic stories of how they come to the lands we’re on, but also encouraging people to think about accountability to First Nations lands we’re on.

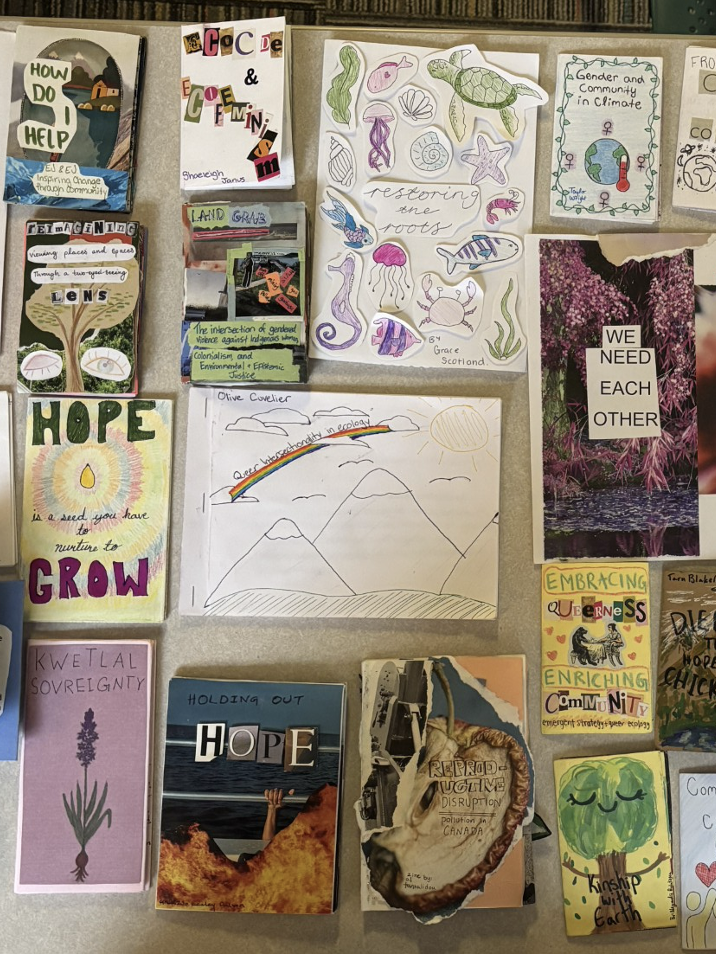

For the next assignment, I’ve collected these beautiful zines. I’m so excited about these. They’re fun at school, they’re political. You can make them different sizes, like an 8.5×11 kind of fold, and then I tell them to go back to “kindergarten vibe” and just cut and paste or draw. I basically have them think with some of the concepts that are important to them, and then to do something different than just writing an essay. I tell the students that art projects kind of scare me because I’m not an artist, but some students really like doing them, and even the ones who don’t, I invite them to collage. Then I invite them to think with two or three concepts they’ve learned in the course and connect them to artistry.

A big part of their course is a group project. One of the goals for this project is to counter the typical models of students as individual grade-getting bodies being judged individually. I tell them why that’s counter to solving environmental problems, given the competitive academic world we’re in. I ask them to do a group case study of environmental (in)justice, which involves different elements: completing an outline together (unevaluated), a group presentation, and a group report that has to have all those parts I mentioned before: grounding in the lands where the case is, trying to centre hope, transformation, not just doom and gloom, and seeing whose knowledges count in those places. This one term, I’m doing a final exam too (to try to evade generative AI), but I’m not going to next term.

The last 15% is a self-evaluated engagement portion. Usually, I’m just confirming their honest approaches. Some of them have neurodivergences and different ways of engaging with the course, so they can explain in that document to me what was affecting them and how they were coming to class and preparing.

Fyza Azam: Those sound like some interesting assignments. I’ve never had an assignment like the zine one, that sounds very interesting.

Anita Girvan: Many Gender Studies departments have done zines as a feminist approach to politics and the arts, and most students have loved them. I can see a couple of them didn’t, but it’s only worth 10%, so it’s another way to evaluate, and it’s just fun. The students say that when they’re writing too many essays, they think it’s fun to get off the screen and just cut and paste, or do something creative. It’s really fun for me to mark, too, because essays rarely blow the socks off professors when they’re reading them. When you see creative things, it’s just wow! I should also say that when they’re doing a group report, I also say, “I don’t know what you all have creatively in your toolkit, but creative work is also an option.” I’ve had students at my previous university who composed poetry for their assignments. I’ve had someone paint something. One group did a podcast, so that’s always an option for my final projects, which allows people to bring their own creative ideas to it, as long as they’re engaging with the course as well.

Fyza Azam: Is there anything else you would like to tell me about the course?

Anita Girvan: I would say students have a big role in my pedagogy. I think with students. This syllabus evolved quite swiftly after the 2023 wildfires in Kelowna, so that was where my pedagogy towards hope came in. I was feeling pretty hopeless. Having taught youth for maybe 15+ years, I was feeling, “How am I going to teach this now if I’m feeling like the wildfires are too close to feel the presence of climate change?” I was like, “I can’t teach this course the same way at all. I have to start with whatever I can find about hope, and I don’t want it to be white folks’ affect of hope like about neoliberal care for the self and going to the spa and whatever.” I was looking for critical versions of hope. People like Mariame Kaba, a Black feminist, are watching the death of Black folks around her all the time, and she says that apathy is a luxury we don’t have. You can’t just be cynical. Cynicism and apathy, we can’t do that, because it’s like throwing your hands up and saying the state of the world is okay as it is.

Other versions of hope were produced by more-than-human encounters with wildfires. That’s been a great pedagogical shift that came out of wildfires. I look for inspiration from more-than-human elements, including wildfire, and then students. I feel like my pedagogy is very responsible and responsive to students who have helped shape my teaching.

Fyza Azam: Thank you, that was the final question.

More about Dr. Anita Girvan.